Val Shaff is a photographer who worked for years in New York. We already knew each other in our private lives, and had shared long conversations about the creative process — how projects begin, the questions that lead them forward, the idea of finding our voice, building a body of work, the doubts… When I imagined this series, I knew right away I wanted to sit down with her.

When I sent my first round of invitations to artists, Val booked the very first slot. That’s exactly who she is: efficient, spontaneous, always ready to dive in — generous, forgiving. Beginning with her felt like a relief.

The first time I visited her studio, I was struck by the light in the space, and by how everything seemed set with intention — archive files, a big island table in the middle so she could flow around and spread the work, a dedicated area for her computer and professional scanner. I remember thinking: If I were a photographer, this is exactly the kind of space I would dream of.

Val’s work with celebrities and their animals has been featured on the covers and in the pages of too many magazines to be listed. She’s photographed musicians, writers, actors, dancers, children, and yes, animals — though it would be unfair to pin her to just one subject. Her images are less about the category and more about a search for presence: a way of capturing the spirit of beings in motion, in relation, alive in front of her lens.

She welcomed me one gloomy morning in her studio, and that’s where our conversation began — sketching together the first lines of the NY Creatives map.

Hello Val, thank you for having me in this beautiful space. Can you tell me what first brought you to photography?

I grew up in a family where photography was part of our good times—not by making group pictures, but because the highlight of our family life was traveling. It was very important to my father that we see the world. He made home movies that were quite elaborate, with soundtracks and music, carefully edited by hand. My mother, though she didn’t consider herself an artist, made still photographs out of her own interest in family and place. So that was natural to me.

I thought I’d be an illustrator or a painter.

In high school, I learned to process my own film, reactivated an abandoned darkroom, and spent every spare minute there. At Bard, I started out as a painting major, but I never felt in sync with the department’s values — they frowned on my interest in representational work. Meanwhile, I was always in the darkroom. When Bard created a photography department, I became its first photo major. That gave me a real way to build a body of work. What drew me most to photography was the chance to document my own life, and that passion has stayed with me.

We’re in your studio now. It’s filled with light. What do you feel when you walk into this space?

It varies. Sometimes I see all the archives I’ve produced but haven’t fully explored, and it’s overwhelming. Other times it’s just an office. The best times are when I’m actively working on a body of work—I can’t wait to get back to it. I also sometimes feel guilty having such a great studio, when in the past I made do with so little. Paradoxically, it can feel harder now to access creativity.

What inspires me most here is what I see outside the windows. I’ve always looked outward for inspiration; what’s inside is my emotional response. I’m not a conceptualist interested only in my own thought process.

Some people say they need a space before they can create. You seem to suggest the opposite.

I do appreciate the studio, but I believe necessity is the mother of invention. A friend once said her creative practice is all about restraint—that resonated with me. Often, limitations or constraints bring the most energy. Now I’m trying to embrace other kinds of containers—community and regular practice. That’s why I’m excited to be involved with CPW and the class I’ll be working with this fall. (Photobook I: Making a Book Dummy by Adrianna Ault at CPW NDRL)

Do you have a specific memory of who or what shaped you most as an artist?

Not really. I’ve mostly followed my own heart. My influences come more from the history of painting than photography. I have a romantic view of life and prioritize feelings over intellect.

I know that you’ve been working on your archive. What happens when you revisit your work?

It’s both revisiting memories and discovering them anew. Scanning negatives feels mechanical, but surprises appear. I might recall when something happened, but as I refine the images—crop, adjust exposure—connections emerge across years. That helps me clarify my life’s work and see more coherently.

Do you recognize yourself as the same photographer today as in your early portraits?

Yes. My vision is pretty singular and consistent. My images are clean, direct, very much about the subject. That’s how I am too.

Do you feel your creative process helps you understand yourself?

Yes. I’m very intuitive when making photographs. I don’t over-conceptualize. I may get excited about a person or place, but once I start it’s instinctive. Editing is when I become more discerning. Looking back at old images now gives me a bird’s-eye view. It helps me see continuity in my vision.

Talking about intuition, do you sometimes have the immediate sensation, in the very moment of clicking, that an image is special?

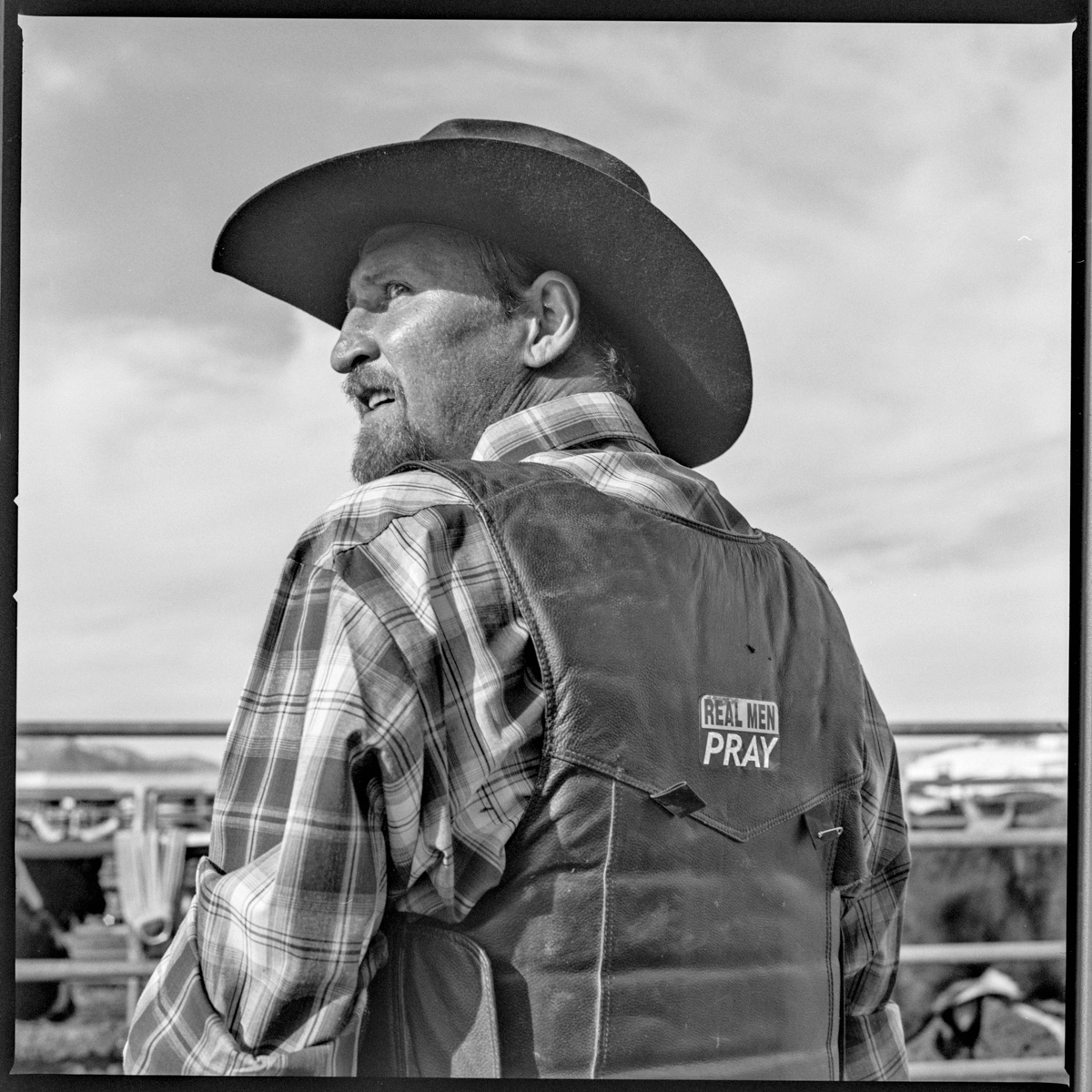

Definitely. I rarely alter my photographs. They’re classical—usually full-frame. I often know when I’ve made a strong image, though it can happen at the start or only after going deeper into a shoot. Sometimes it’s about reframing until the essence emerges. For example, at a rodeo I photographed young men about to risk their lives bull riding—their authenticity was striking. Going back to those images years later, I rediscovered their intensity. There’s a continuity in my vision, even as subjects change.

I have a mystery box with questions from different people. Questions they have always wanted to ask an artist. Can you pick one?

“When does inspiration visit you, and how do you invite it in?”

Travel has always motivated me, but I also love the familiar. I like moody light, not bright sunny days. Different things inspire me—sometimes strangers, sometimes places I know well. Often it’s about deliberately putting myself in circumstances that will inspire me. Many of my images are solitary landscapes. Others are about relationships. Both inspire me in different ways.

I want to draw a map of NY creative souls. I believe in webs and connections. Who should I interview next?

My good friend Lisa Durfee. She’s one of the most creative people I’ve known. She wouldn’t call herself an artist first, but her life and her creative output are deeply consistent. She runs a vintage clothing store in Hudson called Five and Diamond. Everything she does involves recycling her environment—clothes, old wallpaper, collages. Even dryer lint from her vintage clothes became an art piece. She goes mudlarking and collects artifacts. Her life is an ongoing creative practice. I so admire that.

Our interview ended by opening a new door—onto creativity, onto ways of interpreting the world. I left grateful for that hour, surrounded by images and stories that will stay with me.

Follow Val’s work :

Instagram : valshaff