Understand what is Tapa in Polynesian Culture

Tapa is more than cloth—it’s memory, connection, and ceremony woven from the bark of trees.

In Polynesian culture, tapa (also known as aute, siapo, kapa, or u‘a, depending on the island) is made by the women, passed through hands and generations, and used in the most meaningful moments of life.

It carries not just patterns, but stories.

Tapa is present when a child is born, when two families unite in marriage, and when someone passes away. It wraps bodies, gifts, and ancestors.

It marks identity, rank, and respect.

Creating tapa is an act of patience and precision—beating the inner bark of the mulberry tree, joining fibers, dyeing with natural pigments, and imprinting symbols that often echo genealogy, territory, or spiritual beliefs. But beyond the technique, the act of making tapa is deeply

communal. Women come together to work, sing, and share knowledge.

The process becomes a space of social cohesion and feminine power.

Tapa is ephemeral yet enduring. It can tear, rot, disappear—but its role in Polynesian societies is unbreakable.

Even today, though used less in daily life, tapa continues to be made for rituals, gifts, and remembrance. It survives as a fabric of belonging—connecting the living to their ancestors, and the individual to the collective.

My Interpretation

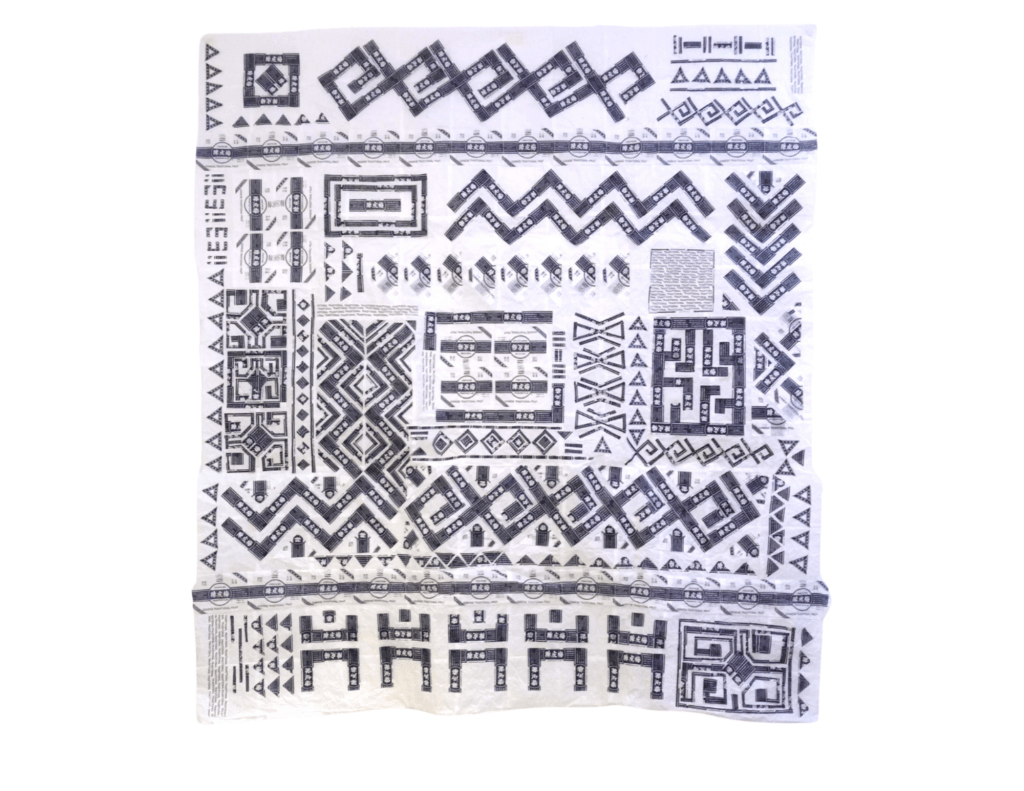

With Tapari‘i, I wanted to revisit the themes of identity, rank, and respect—central to the meaning of tapa—and explore how they apply to my own story.

I have Chinese roots. Both of my maternal grandparents are Chinese, and even though I was raised in Tahiti, and all my family still lives there, we don’t have Polynesian blood. This sometimes brings up the question of belonging _ Where do I stand in the cultural fabric I grew up in?_

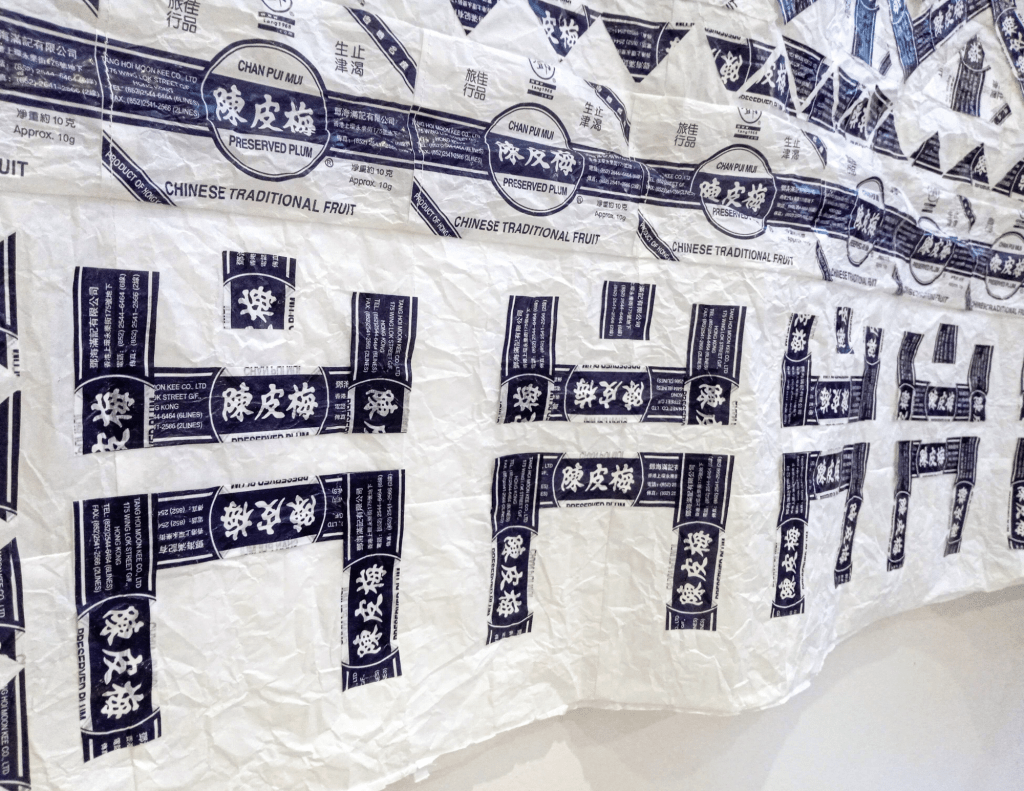

So I decided to create a tapa that would weave together these two civilizations—Polynesian and Chinese.

Instead of using traditional materials and ink, I used Chinese candy wrappers. Their printed designs became my patterns. I imagined the wrappers as a form of bark cloth—fragile, shiny,

mass-produced, but also intimate and deeply nostalgic.

An unexpected detail emerged: the blue ink on the wrappers formed clean, straight lines. So the patterns I composed didn’t mimic Polynesian motifs; they looked unmistakably Asian!

At first, I worried this might move the work too far from tapa. But then I remembered—Polynesia has Asian ancestors. The lines between cultures aren’t always borders; they can also be threads.

Tapari‘i became a personal reconciliation—a way to honor both the culture I was raised in and the one I carry in my blood. It’s a tapa that doesn’t claim tradition, but reimagines it. It asks: What if identity isn’t about choosing one heritage over another, but about holding space for both?

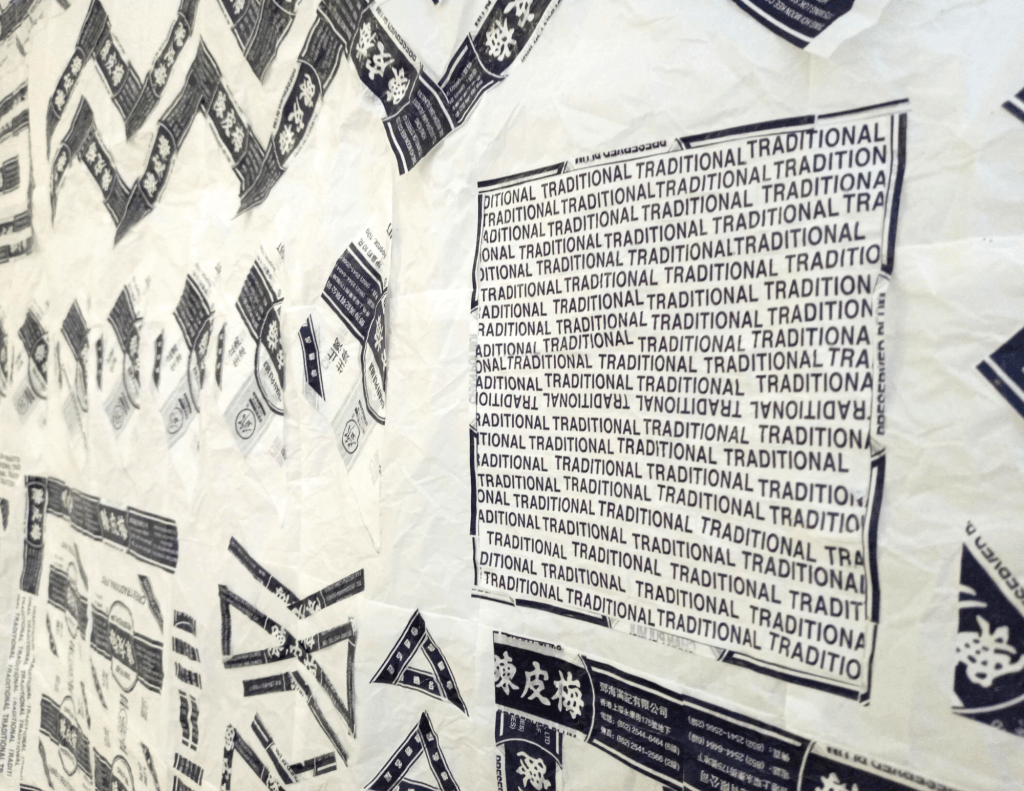

If you look closely, Tapari‘i also hides a few easter eggs.

The candy wrappers I used were all printed with the word “traditional”—over and over again, impossible to ignore.

That repetition stuck with me.

It felt like a reminder, but also a weight. Tradition can be beautiful and grounding, but it can also become a wall — impressive, even oppressive.

So I made one small move. I flipped a line upside down.

It’s almost invisible. Most people won’t notice it. But it’s there—a quiet shift, a gentle push. A way to mark the possibility of change, of rethinking what tradition allows. A nod to anyone who feels the urge to do things differently, but fears they don’t have permission.

This upside-down line is for them. For us.

Polynesian tapa often includes many symbolic representations of the human figure. These motifs are more than decoration—they speak of lineage, protection, presence.

In Tapari‘i, I chose to create five human figures. They’re a quiet reference to the five archipelagoes of French Polynesia: the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Tuamotu, the Gambier, and the Austral Islands.

This is also a nod to the five stars on the Polynesian flag, each one representing a part of the larger whole.

Through these five figures, I wanted to express unity across distance—how each archipelago carries its own identity, yet they all belong to the same body. Much like the different cultural elements I’m weaving together in this piece.

It’s a way of anchoring the work back to where I come from, while still leaving space for where I might be going.

I also included Marquisian crosses—those powerful, geometric crosses that are so distinctive in Marquesan design.

They’re often carved into stone, wood, or skin, and they carry a strong spiritual weight. The Marquisian cross can symbolize balance, connection between the elements, or the guiding presence of ancestors.

To me, they represent anchoring—something steady at the core of movement and change.

By integrating these into Tapari‘i, I wanted to pay tribute to one of the most visually and spiritually rich traditions within Polynesia. And at the same time, I was asking: What happens when we take these ancestral symbols and place them in a new context—wrapped in candy paper, in a hybrid tapa?

It’s not about desecration. It’s about conversation.

Between past and future, between cultures, between who we are and who we are becoming.

Tapari‘i is not a tapa in the traditional sense.

It’s not made of bark, nor painted with ancestral pigments. But it carries the weight of tradition, the questions of identity, and the desire to belong—even when the lines don’t align perfectly.

The name Tapari‘i comes from a joke I used to make—a mix between tapa and tamari‘i, the Tahitian word for “child.” Like a tapa-child, this piece is both an homage and a playful reinvention. It’s a child of two cultures, raised in between worlds, curious and slightly mischievous, trying to find its place while rewriting the rules.

By weaving together Chinese candy wrappers and Polynesian symbols, I wanted to explore what it means to grow up in one culture while carrying the legacy of another. What it means to honor traditions without being bound by them. And what it means to take part in a visual language—

even if you speak it with an accent.

This piece is personal, but it’s also part of a larger story—a story of movement, of blending, of quiet resistance and creative inheritance.

Like the flipped line hidden among the patterns, Tapari‘i doesn’t shout. But it asks. It invites. It makes room.